PHOTOGRAMMETRIC ENGINEERING & REMOTE SENSING

July 2018

413

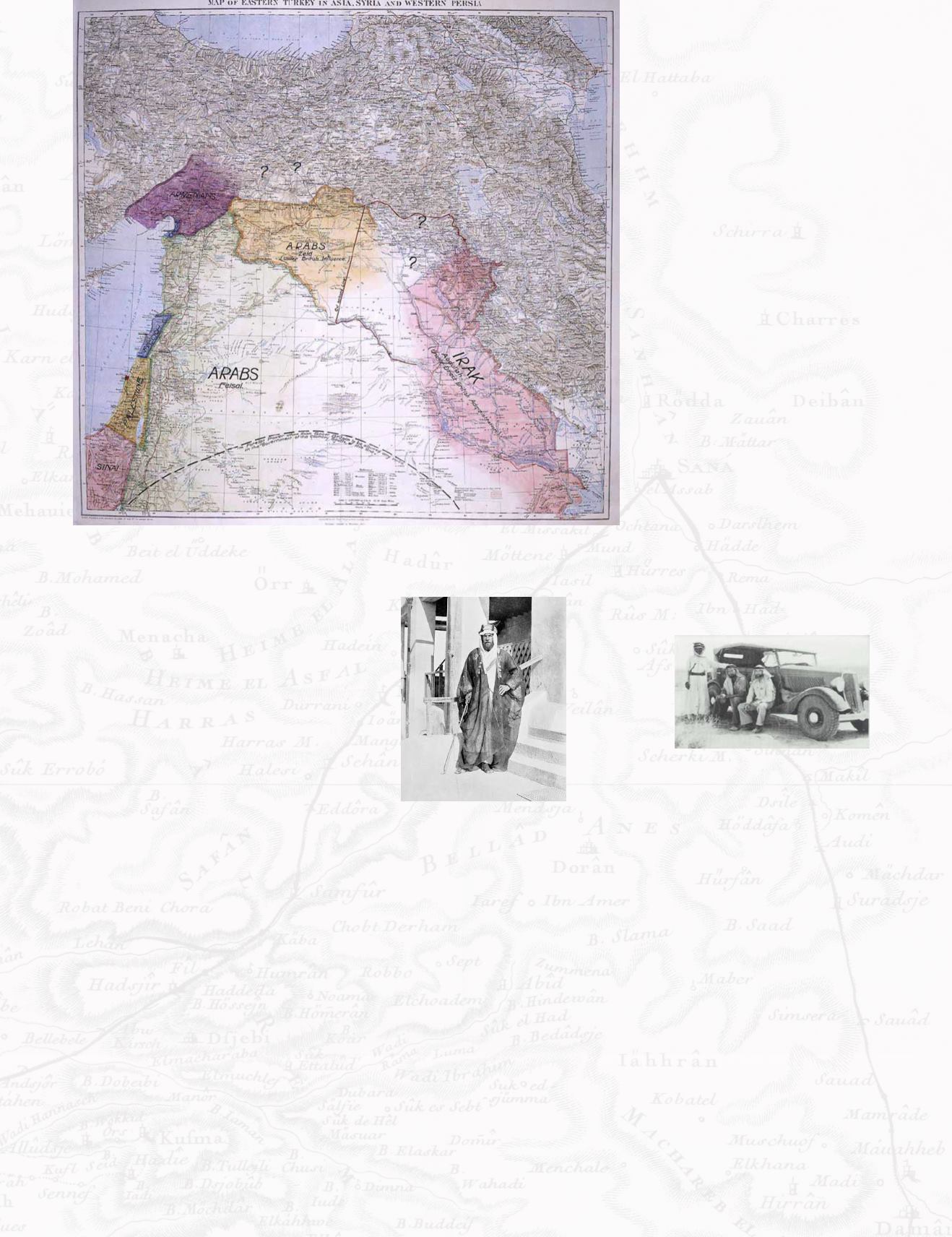

Figure 5. By T. E. Lawrence - British National Archives, Public Domain,

One of the difficulties of mapping large

areas is the ability to not only mea-

sure distances but accurately convey

bearings of measurement. The mod-

ernization of the theodolite, the first

instrument to obtain both vertical and

horizontal angled measurement, al-

lowed these measurements to be taken

in the field. By the late 1880’s, this

surveying tool along with later manifes-

tations of the William Burt Solar Com-

pass, allowed Lawrence and Philby, to

map large areas of northern, western

and southern Arabia around the time of

the first world war. However, accurate

distance remained allusive, and often

needed to be equated from camel hours

or as the French Voyagers did, by the

time it took to smoke a complete pipe

full of tobacco.

The Oil Boom

Following the oil shortages of WWI and

the burgeoning economics of the au-

tomotive century, the western powers

were increasingly interested in discov-

ering and monopolizing new sources.

Given the many naturally occurring oil

seeps in western Persia, the Gulf sepa-

rating the Arabian Peninsula and what

is now Iran, became a hot bed for ex-

ploration. In May 1932, Standard Oil of

California (SoCal) struck oil in Bahrain,

which immediately brought the interest

of exploring (and mapping) the here-

tofore unexplored Eastern Province of

Arabia. Both the Americans and British

(Iraq Petroleum Co), each with their own

concessions in the region, were eagerly

vying for the right to do so. The British,

with their WWI governmental liaison

Harry St. John Philby acting as the sole

western advisor to King Abdul-Aziz

ibn Saud, thought that they already

had the upper hand. However, because

of Philby’s resentments over Britain’s

broken promises to the Arabs with the

Sykes-Picot Agreement, he treacherous-

ly handed the concession to the Ameri-

cans on May 29, 1933. (Figure 6).

Within a year, the Americans had sent

geologists, engineers and surveyors to

the region, to explore, map and locate

the most opportune sites for drilling

test wells. Although they could ship

all the most modern equipment, the

first Americans were ill prepared for

the realities of mapping in the extreme

heat, humidity and sand conditions of

the Eastern Province. A number of local

Bedouin guides were provided by the

Amir of Dammam, these men became

known as the ‘relators’ and they pro-

vided a living geographic encyclopedia

which allowed Arabia to be mapped.

Even so, going was a slow slog through

sandy dunes even in vehicles with over-

sized tires.

To speed up the process significantly,

the Americans convinced the King that

the best way to find areas of potential

oil, was to map the peninsula by air.

Dick Kerr, an ex-US Navy pilot operat-

ing one of the first aerial mapping busi-

ness’ in the US (located in Los Angeles)

was asked to take on the contract of

obtaining aerial photography and pro-

viding air support for ground surveyors.

Deeming that a smaller plane would

fare better in landing among the

sinuous salt flats between high desert

dunes, the company specially ordered

a Fairchild 71 from the Hagerstown,

Maryland factory. A hole was built into

the belly of the aircraft behind the pilot,

Figure 6. Image from The heart of Arabia, a

record of travel and exploration (London:

Constable and Company, 1922) by H. St.

J. B. Philby:

Figure 7. Image from The Search Began In

1933

/ 9 March 2007).